Rwanda Polytechnic’s ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme*’

Tool focus

The introduced tool is an in-company/workplace learning instructor training programme aimed at providing in-company instructors (ICIs) with the pedagogic skills, expertise and knowledge they need to contribute to the delivery of effective Workplace Learning (WPL) programmes.

Target group

The tool has been designed to support employers in their delivery of WPL through the training of ICIs. Target beneficiaries for the tool include employers and their trainers, trainees and apprentices and wider TVET stakeholders delivering WPL. It is anticipated that an understanding of this tool will provide valuable insights for providers across the AU who are looking to introduce guidelines on the capacity building of employer led WPL.

Description of the Programme

There is a growing awareness of the importance of supporting employers in the delivery of effective workplace learning (WPL) including through the development of in-company instructors (ICI). The presented tool, In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme, address this issue through the building of in-company instructor (ICI) capacity to prepare, facilitate and assess WPL4 .

The tool, presented as a ‘Curriculum for an in-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’, was developed in 2019 by Rwanda Polytechnic (RP) as an intervention delivered through the Association for the Promotion of Education and Training Abroad (APEFE), ‘workplace learning support programme’ (IGIRA KU MURIMO) project (2017 - 2021). The project was delivered in partnership with the Ministry of Public Service and Labour (MIFOTRA) and the Private Sector Federation (PSF), with the core objective to promote the introduction of effective WPL models, including dual training.

The ICI programme was developed in consultation with wider development partners, including; EDC (US Aid), GIZ, ICON, Swisscontact, CSC Koblenz, and national TVET and private sector stakeholders. The curriculum is for an 80-hour training programme, split between 40 hours for face-to-face tuition and 40 hours for practical application of learning. APEFE’s external mid- term evaluation report (2020) records 102 ICIs having been trained through the project5 , which exceeds the initial target of 40. The programme is aligned with national initiatives, including the MIFOTRA’s ‘Guidelines on the Implementation of Workplace Learning Policy in Rwanda’ (WPL Guidelines) August 2021, which looks at formalising WPL practice and processes.

WPL Framework

In Rwanda workplace learning (WPL)6 is governed by a legal framework that provides definitions for different types of WPL models:

Workplace learning in Rwanda (WPL) - Definition of terms | |

Attachment (or Industrial Attachment): | An attachment is a compulsory part of an education program, usually implemented in the TVET sector and in higher education. Participants are students, and the successful attachment is a prerequisite for graduation and certification. Although the learning may be structured, the main purpose of an attachment is work exposure by putting into practice what has been learnt before. |

Internship: | An internship is an opportunity offered by an employer to potential employees, called interns, to work at a firm/an organisation for a fixed or limited period in the area related to his/her field of study. The professional internship is not part of an educational learning program, but a freestanding work experience scheme, aimed at easing the entrance into work of Rwandan graduates from higher learning and Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions. |

Dual apprenticeship or Cooperative apprenticeship: | Cooperative training is a modern form of apprenticeship. An important learning location is a company, but the training is complemented by basic, generic and theoretical training modules delivered in a training institution. Usually |

Industry Based Training (IBT) or TVET in companies: | This is a form of modernised traditional apprenticeship where TVET is provided in and by companies. Usually such an enterprise has established a training wing. Training may be delivered by the enterprise owner or by extra employed staff. It is a kind of training centre within an enterprise, hence TVET in companies. |

Rapid Response Training (RRT): | RRT is a form of Industry Based Training organised on a cost-sharing basis in order to facilitate investors willing and ready to invest in specialised or priority skills. The agreement is reached in anticipation of emerging investment opportunities, but at the same time is flexible enough to allow specialised training to be targeted at the needs of investors who are in need of skilled personnel in specific sectors. At least 70% of graduates should be retained by the company that benefited from the training facility. |

Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL): | RPL is a process of acknowledging prior learning acquired in different contexts, especially at work (like traditional apprenticeship |

Source: Guidelines on the Implementation of Workplace Learning Policy in Rwanda’ MIFOTRA, August 2021 | |

Formal WPL

Formal WPL is governed through the ‘National Policy on Workplace Learning to Prepare Rwandan Youth for Employment (Workplace Learning Policy) 2015’.7 Together with internships, the ‘Law regulating labour in Rwanda’ also legally governs apprenticeships.8

The National Employment Programme (2014) promotes the development of WPL models, including apprenticeship schemes9 . The Skills Development Fund (SDF)10 also includes a focus on employer led apprenticeships, internships and short skills upgrading programmes. It is reported that the Hang Umurimo (Create Own Jobs) and Kuremera programmes, implemented by the Ministry of Trade and Industry and MIFOTRA respectively, delivered through apprenticeships, have led to 17,000 people finding employment.11 Many of these apprenticeship initiatives are being delivered in cooperation with Rwanda TVET Board (RTB) and/or Rwanda Polytechnic managed TVET institutions. Development partners also play an important role in the implementation of WPL initiatives.

The delivery of informal WPL is defined by multiple and sometimes disparate stakeholders, with learning often being based on emerging and unstructured assignments.12 Despite the capacity of informal apprenticeships to offer training to a large number of trainees, it is a model that comes with significant limitations. These include concerns about quality with apprentices and trainees being unable to develop competencies beyond those held by their supervising master craftsman, who themselves may have come through an informal apprenticeship. The need to embed and expand workplace supervisors’ expertise is a key driver behind the presented tool. Informal WPL can also be defined by an absence of agreed training programmes and contractual arrangements between employers and trainees, which illustrates the need to build the capacity of employers in both the design and delivery of WPL.

The delivery of WPL through multiple stakeholders, often in informal contexts, has highlighted the need for the introduction of standards and guidelines that regulate and coordinate practices and partners. A response to this requirement has been led by MIFOTRA, who, with support from GIZ, designed a series of ‘Guidelines on the Implementation of Workplace Learning Policy in Rwanda’ (WPL Guidelines) (August 2021), which set out WPL implementation standards for Industrial Attachments, Internships and Dual Apprenticeships:13 ‘The Workplace Learning guidelines outline the procedures that learners, training providers, employers, regulators, and partners must follow to ensure successful workplace learning implementation.’14

Importantly for the ICI development tool described in this report, MIFOTRA’s WPL guidelines include references to employers having responsibilities for ‘ensuring that appointed in-company instructors are trained to be able to facilitate students’15 In this respect, the ICI training programme can be seen as part of a broader national initiative to formalise, harmonise and build capacity for WPL implementation. This regulatory objective is also captured in Rwanda Polytechnic’s ‘Guidelines for developing in-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’, which looks to formalise approaches to ICI development.16

The Tool: ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training program’ Rwanda

Rationale

APEFE’s Workplace Learning Support Programme (2017-21), delivered in partnership with MIFOTRA and PSF, promotes the introduction of effective technical and vocational education and training (TVET) by supporting private sector stakeholders and training providers in the piloting of WPL and dual training models. This has included collaborating with Rwanda Polytechnic in the design and implementation of a pilot promoting WBL models across the TVET ecosystem: ‘the formulation of a programme aimed at skills development, employability and entrepreneurship of young men and women in Rwanda with the stakeholders (beneficiaries, stakeholders, partners, national structures).’17 Amongst its objectives, the pilot focused on the development of private sector employers to play a full role in the TVET sector, including through ICI training, to ensure the ‘quality training of apprentices in the workplace.’18

This focus led to the design of the presented tool; ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’; ‘To ensure that the WPL training is effective it is a great advantage that companies have competent staff members that can engage in the learning of the trainee.’19 The programme looked to develop a cadre of ‘dual professionals’, who possess the technical competences and pedagogic confidence to successfully train, monitor and assess trainees and/or apprentices. It was also envisaged that the embedding of pedagogical competencies in the private sector would have the secondary benefit of enhancing companies’ capacity to deliver wider HR development activities.20

Description and background

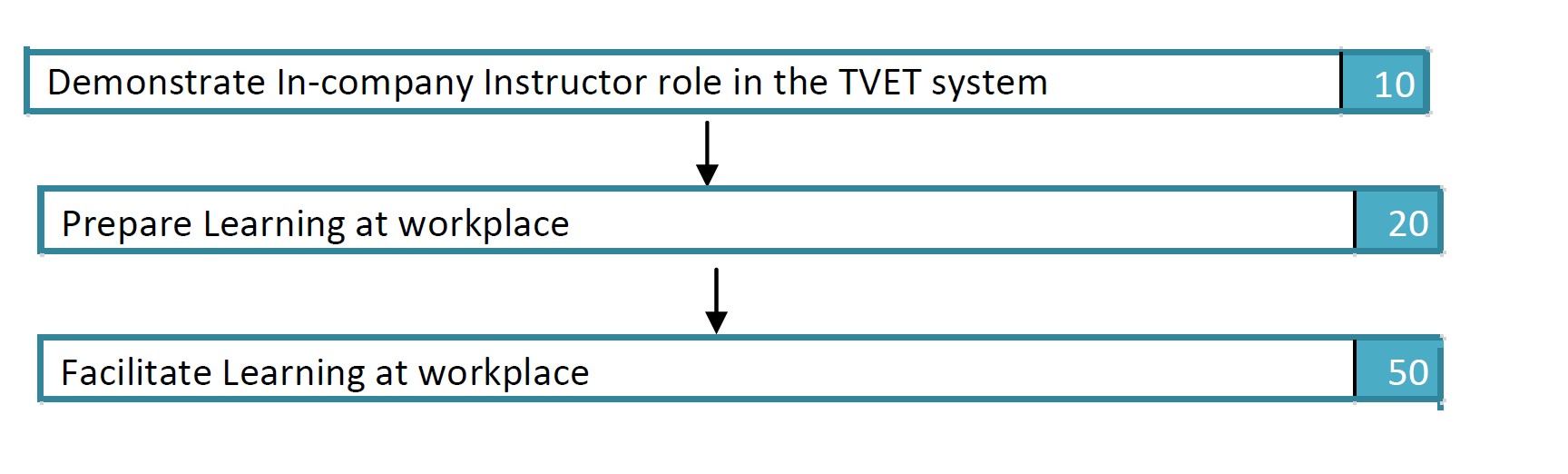

The ICI training programme covers competencies in a range of tasks and activities related to the delivery of WPL, including the role of ICIs in the TVET system, preparing for learning at the workplace and facilitating the delivery of WPL. The tool is presented through the Rwandan Polytechnic document ‘Curriculum, In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme, Rwanda Polytechnic (2019)’21 , which provides an in-depth description of the programme:

- Background information related to rationale, entry requirements (employers and ICIs), and the definition of key concepts.

- Overview of the training ‘package’ through a schematic representation of the order of acquisition, and key development areas: communication, teamwork, problem solving, initiative and enterprise, planning and organising and self-management.

Source: Curriculum, ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’, Rwanda Polytechnic (2019), page 5.

- Assessment Guidelines

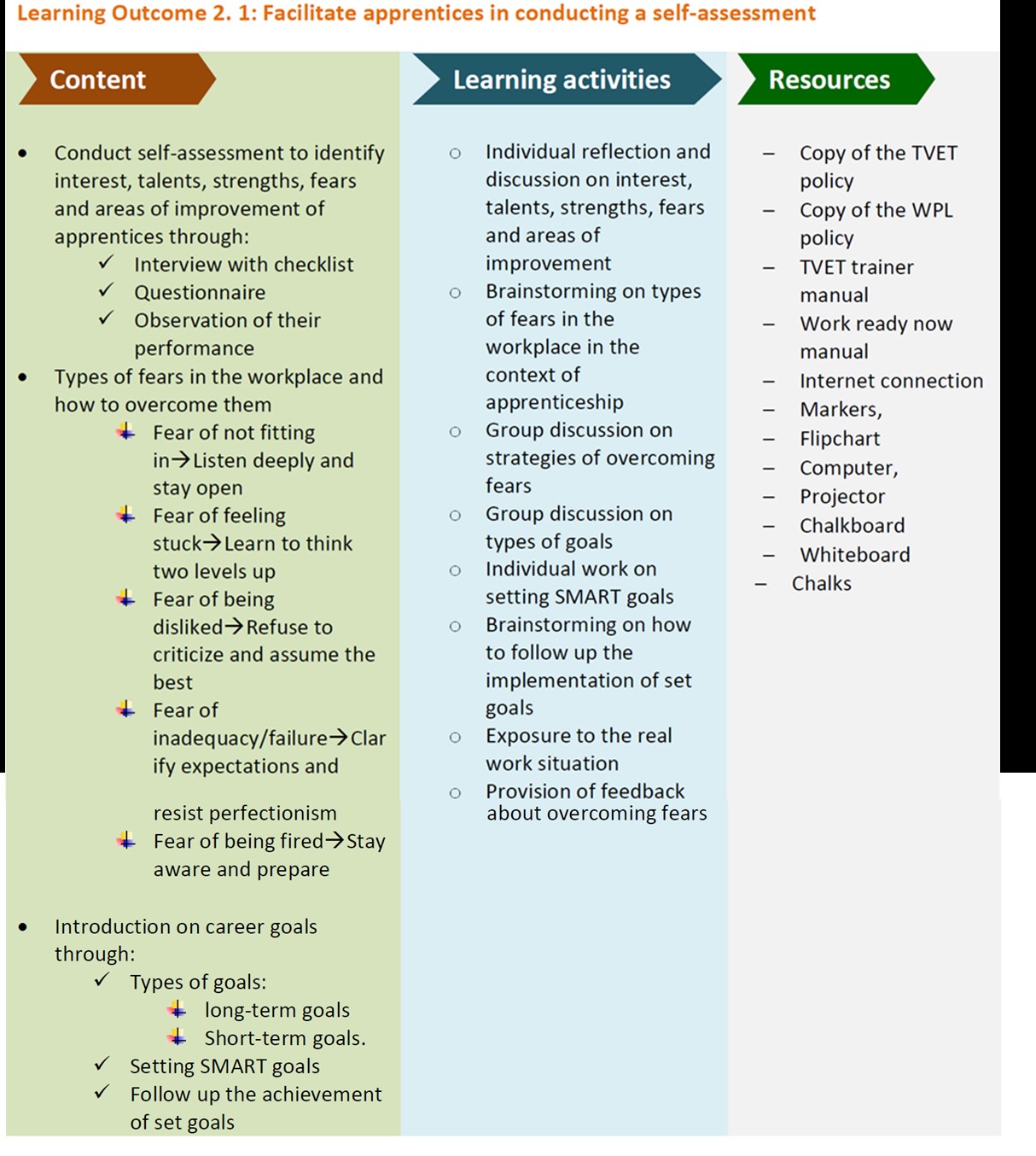

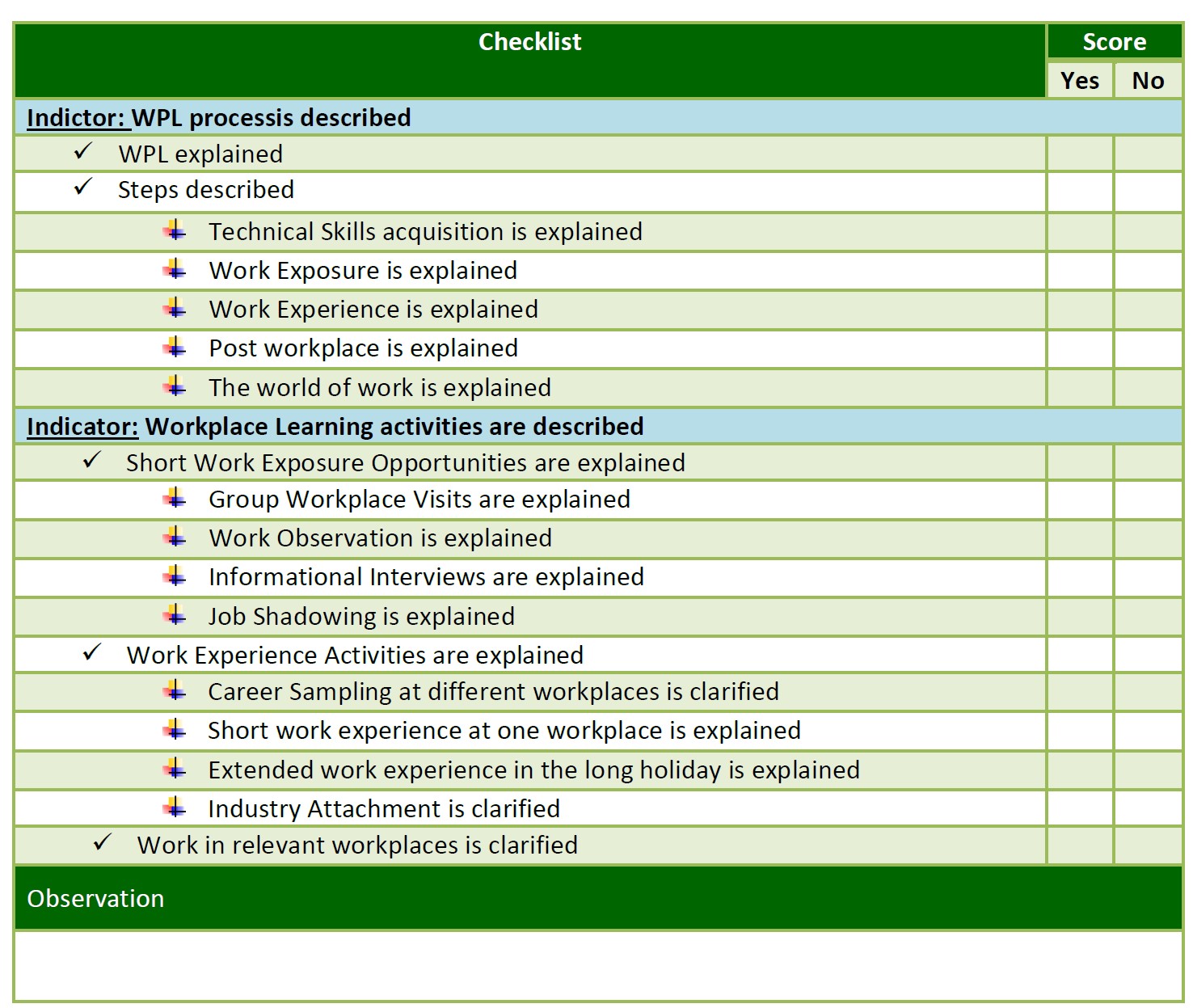

- Overview of modules and details on contents, learning activities and resources checklist

Source: Curriculum, ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’, Rwanda Polytechnic (2019), page 19 - 20

The programme’s target group is experienced (three years minimum) ICIs who combine their technical work-based roles with WPL activities and responsibilities. The programme focuses on providing ICIs with the pedagogic skills, expertise and knowledge needed to improve the quality of training, learner support and assessment conducted in their companies. It also aimed to grow their overall awareness of TVET and their role within the sector.22

The course is delivered through an 80-hour programme, divided between a 40-hour face-to-face training programme, delivered over five days, and 40 hours of practical application (‘practice’) in the ICIs’ workplaces. To ensure strong employer input and support, the design and delivery of the programme was conducted in close cooperation with Rwanda’s Private Sector Federation.23

The tool includes guidance on selecting appropriate companies whose ICIs would be applicable for the programme. This includes criteria such as a willingness to engage in WPL, commitment to ICI development through releasing staff for training and plans to recruit trainees/apprentices. This application of employer-based criteria for ICI selection will ensure that the programme is focused on organisations who are committed to strong and quality based WPL. The tool also includes guidance on the selection of ICIs, through criteria related to: current role, experience and qualifications, and enthusiasm to contribute to WPL. The identifying of ICI criteria, aligned with training, would support a sense of professional identity and the establishment of a network of employer based WPL expertise

Delivery and assessment

The ICIs are assessed after the five-day (40 hours) face to face contact part of the programme, following which they are issued a ‘temporary certificate of completion’. This certificate is only valid for one year to encourage ICIs to progress to and complete the practical assessment stage. The ICIs practical skills are then then measured through an assessment of the WPL delivery in the training context. Following the successful completion of this period, based on submitted performance evidence, portfolios (ICIs and apprentices/trainees), logbooks and work-oriented interviews, a certificate of competence is issued. The programme has identified the use of portfolios as a valuable medium for the development of ICIs, by allowing participants to collect records of work that they can utilise in their ongoing WPL roles and supporting their professional awareness and growth by identifying their strengths and weaknesses. The use of portfolios also requires ICIs to consider how they record, develop and track their apprentices/trainees learning and progress. The assessment of ICIs conducted through the review of submitted portfolios is supplemented by a practical assessment that tests the application of acquired skills based on an observation checklist. This assessment process is conducted through a panel made up of representatives from Rwanda Polytechnic and PSF to ensure a balance between both TVET and employer perspectives.

The programme is delivered through a series of three modules aimed at realising the programme’s competencies flowchart:

1. Demonstrate in-company/WPL instructor role in the TVET system

- Describe TVET system in Rwanda

- Information on the Rwandan TVET system, with associated roles and responsibilities

- Orientation and guidance of apprentices/trainees

- Approaches to effective orientation and guidance of apprentices/trainees

- Mentoring apprentices/trainees

- Application of concepts of mentorship at the workplace

- Provision of induction, support and motivation to apprentices

- Inclusive approaches to WBL

2. Preparation of Workplace Learning (WPL)

- Preparing schemes of work, training schedules and assessment tools

- Interpreting curriculum structures, preparing schemes of work to align with module specifications

- Developing training to reflect schemes of work and workplace job roles,

- Preparation of appropriate assessment tools

- Preparing job/task sheets and training materials

- Develop job/task sheets based on nature of work and tasks to be done

- Develop associated training materials related to job/task sheet activities

- Setting up workplaces for the delivery of WPL

- Collect required materials, tools and equipment required to deliver identified tasks

- Apply legal regulations and guidance associated with the workplace learning environment

3. Workplace Learning (WPL) facilitation

- Conduct WPL briefings

- Clarify objectives, rules and work expectations

- Describe delivery of WPL tasks (and stages to reach completion)

- Explain apprenticeship agreements in line with company policy

- Mentor apprentices in the workplace

- Apply effective inclusive and learner-centred mentorship techniques

- Share the correct application of soft skill requirements aligned with work context

- Facilitate competence-based assessment

- Conduct and evaluate effective competency-based assessment aligned with curriculum guidelines

- Completing WPL activities in line with planned tasks and objectives

- Through a focus on supply-side stakeholders, the key role of employers in delivering and assessing WBL can be neglected in WPL development interventions. This programme directly addresses this challenge by targeting capacity building of ICIs. This will have a direct impact on the quality of employer-led WPL for the direct benefit of the intern/apprentice and the secondary benefit of enhancing employers’ wider HR development activities.

- The programme acknowledges the importance of engaging with private sector partners in programme design and delivery. This includes through close collaboration with employer representative organisations in the case of Rwanda the PSF, chambers of commerce and employer associations in the design, delivery and assessment of ICI training. This approach will support employer ‘buy in’ for the programme. The use of introductory materials explaining the benefits of ICI development and the wider impact of WPL will also support employer engagement and support.24

- The programme is manageable for the participating companies in that face-to-face tuition where the instructor has to be away from the company is limited to 40 hours. In addition, the programme itself applies a WPL training method in that the second part of the programme is carried out at the company.

- The application of selection criteria for the participating ICIs will help to develop a cadre of ‘dual professionals’ embedded in industry who have both technical and pedagogic skills. This group could act as champions, within their companies and sectors, promoting good WPL practices and for the on-boarding of new staff members.

- Similarly, the use of criteria to identify participating companies will reinforce guidelines on the employers’ role within WPL in terms of commitment, contracting and resourcing etc. The alignment of this initiative with the introduction of national guidelines will support strategic objectives to formalise and harmonise WPL approaches and activities. This includes through Rwanda Polytechnic defining its own guidelines for the programme25

- The programme delivers the training through practical and innovative use of checklists and portfolios, supported through practical lists of learning activities and resources.

Source: Curriculum, ‘In-company/workplace learning instructor training programme’, Rwanda Polytechnic (2019), page 19 - 20

- The programme’s assessment approach combines the input and practical parts of the programme through the innovative use of ‘temporary certificates.’ Practical assessment is also conducted collaboratively by both TVET and PS representatives, assessing trainees from both education and employer perspectives.

- The ICI's use of portfolios to collect evidence of practical application of training enables them to successfully complete their training while developing resources and tools to use in their subsequent training assignments.

- An interesting development has been the exploration of the potential to digitise the course contents as a mitigation to the slowdown resulting from the impact of COVID-19. This has included the drafting of Terms of Reference for the development of the in-company instructors’ manual into digital and interactive content. Although this initiative is still being developed it demonstrates the opportunity to further disseminate and utilise the contents.26

- The course also includes a focus on how ICIs can have a positive impact on promoting inclusive training models and workplace practices.

- It is important that such a programme be conducted within a partnership between a TVET institution and an employer’s representative organisation. The TVET institution should have the capacity to provide the needed training and support to companies and ICI during the in-company training phase. The employers’ organisation should have the capacity to encourage employers to engage in the programme and to proactively engage in the constant modernisation of the programme in accordance with developments.

- There could be potential challenges in transferring some of the programme’s features to wider informal sector partners, for example, some of the criteria used for employer selection may be difficult to realise amongst SMEs and MSMEs. Consequently, the programme, in its present form, is directed toward larger companies that understand the value of skills development.

- It would be valuable to have further information on practical steps in ‘scaling up’ the programme. It is noted that the tool was developed as part of a pilot but the initial target of 40-trained ICIs feels modest and it would be good to understand planned approaches for dissemination of expertise.

- There is a potential issue with the assumption that employers (and ICIs) will be able to access the required resources and equipment to deliver the WPL as defined in the programme. This could be a significant challenge for some participants.

- Although the programme includes input on the Rwandan TVET sector, and ICIs’ role within it, there could be further practical examples of how ICIs could link to wider TVET stakeholders, e.g., school/college instructors, through practical examples and events

An evaluation of the ‘Workplace learning support programme’, ‘Tracey (sic) survey on graduates of 4 TVET schools supported by ‘Igira Ku Morimo’ programme’(November 2020) shares some insights into the project’s impact27. The evaluation describes the project’s ‘capacity to foster and bridge the companies’ capacities and the apprentices’ skills’ and that most informants now have a better understanding of the objectives, processes and commitment of WPL, including the specific responsibilities for ICIs in terms of training and supervising apprentices.

The positive reaction towards the project’s tools is also captured in APEFE’s ‘External Mid-term evaluation mission of the workplace support program in Rwanda28, Evaluation Report, Executive Summary (March 2020)29 . It records ‘At ground level, in-company instructors and TVET teachers are satisfied with the value of the capacity building activities supported by the program and their value for their own knowledge and professional skills.’ The report describes how the programme has allowed companies to understand the value of investing in their ICI resource and enhancing the quality of apprentices’ supervision and skills acquisition.

The mid-term evaluation also raised some important challenges concerning the implementation of ICI capacity building initiatives. This includes the need to supplement instructor development by ensuring the availability of appropriate training equipment and materials; ‘There are issues regarding the availability and appropriateness of the equipment at the companies, which are for some under-equipped to train apprentices efficiently.’ There were also challenges in establishing common practices between ICI and TVET teachers and how these links need to be further strengthened through increased collaboration and knowledge sharing. The report also referenced that despite much progress, there remains some confusion in companies about the specifics of dual training and its successful operationalisation; ‘There is actually diverse understanding of the dual training specificities by the stakeholders, specifically the TVET schools and companies.’

Most importantly, despite these challenges there are testimonials that describe the positive impact that the project has on learners’ opportunities and outcomes; https://www.newtimes.co.rw/news/apprentice-vulnerable-youth