Human Resource Pioneer Firm Certification System

Initiative focus

The core objective of the certification system is to provide a mechanism to register and promote enterprises who are consciously and conscientiously training their employees and, by doing so, promoting decent work and improving the social images of workers in MSME industries.

Target group

Employers engaged in apprenticeship

Introduction

The Skills Initiative for Africa (SIFA) is a project implemented by the African Union Commission (AUC) and the African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD) with the support of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KFW), the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the European Training Foundation (ETF). SIFA is co-funded by the Bundesministeriumfür wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (BMZ) and the European Union (EU). SIFA aims to promote the occupational prospects of young Africans through the support of innovative skills development programmes and in close cooperation with the private sector as an integral and key stakeholder in the creation of jobs. One of the key activities of SIFA is the creation and dissemination of knowledge on topics relating to employment-oriented skills development through exchange and dialogue formats. These take place through the African Skills Portal for Youth Employment and Entrepreneurship (ASPYEE) and through regional and continental event formats such as Africa Creates Jobs (ACJ). Learning offerings, knowledge products and tools shall support SIFA’s audience in facilitating skills development on the continent. SIFA’s audience includes political decision and policy makers, private sector associations and other entities, TVET practitioners and other stakeholders involved in skills development and youth employment. The final beneficiaries of the programme activities are African youth. The African Union’s (AU) Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Decade Plan of Action focuses strongly on enhancing the quality of apprenticeships and engaging with the private sector. SIFA supports the implementation of the action plan and, via its ASPYEE portal, disseminates knowledge on existing approaches towards implementing apprenticeships in Africa, including lessons learnt.

A comprehensive overview of the varying apprenticeship tools in the form of approaches, models, procedures, forms etc. that are used in the African countries and easily accessible is missing. Easily accessible apprenticeship supporting tools and guidelines shall enable governmental TVET authorities, skills development practitioners in the private sector, TVET colleges, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGO) and Development Partners (DP) to improve the design and implementation of apprenticeship programmes and initiatives.

It is against this background and guided by a research and mapping concept2 that SIFA has supported the identification of practical tools applied that has facilitated the advancement and implementation of apprenticeships in selected AU member states. This paper is part of a series of papers presenting and discussing apprenticeship-facilitating tools used within a diverse selection of apprenticeship programmes implemented in different AU member states. The papers' introductory TVET sections do not claim to be exhaustive. They serve solely to provide context for the sections presenting the apprenticeship programmes and tools. The tools do not necessarily represent the most advanced tools but rather robust examples that could be applied by apprenticeship projects at different stages of their advancement.

It is in this context that apprenticeship in Sudan was analysed to identify practical apprenticeship facilitating tools.

TVET in Sudan

Sudan’s formal TVET system3

Figure 1Formal Sudanese education system

Source: Guide to the Vocational Training System in Sudan’ Supreme Council for Vocational Training and Apprenticeship 2021. www.scvta.gov.sd

Basic education students may enter formal TVET programmes offered by the Ministry of Education or the Supreme Council for Vocational Training and Apprenticeship (SCVTA).

TVET programmes under the Ministry of Education:

- TVET programmes under theBasic education graduates can enter technical secondary schools (TSS). There are four types of technical secondary education: women, commercial, agricultural, and industrial. According to the Ministry of Education's homepage, students on the three programmes receive 40% of their training as basic theory and 60% as practical training. After three years, students sit for a technical secondary school exam, and successful candidates can then apply to universities if they meet the entry requirements.

- Basic education students who do not pass the basic exam can enrol in craft schools. Some craft schools have their own buildings and facilities. Others will be organised within TSS using their facilities. The student receives 30% theoretical input at the school, and 70% practical training at an employer, after which they are awarded a certificate of completion and can join the labour market as a skilled worker. They may also join six months bridging course, which if they pass (a score of at least 60%), they can join TSS to obtain the three- or two-year diploma.

TVET programmes under the Supreme Council for Vocational Training and Apprenticeships:

- Basic education graduates under the age of 20 may also apply for a three-year apprenticeship programme offered at vocational training centres (VTC) equal to a total of 3,870 hours (1,000 hours per year for two years, then 1,650 hours for in-company training (42%) and 220 hours at the VTC in the third year). After completing three years, trainees may sit for the standardised apprenticeship diploma exam after which they can enter the labour market as skilled workers. Graduates may also enrol in technical colleges or even universities if they pass the qualifying exam4 .

- Students who have not passed the basic education exam can join other training courses at VTCs. This may be on one of two apprenticeship programmes or short training courses:

- A two-year apprenticeship programme which has a total of 2,200 hours (800 hours per year for two years and 600 hours of in-company training divided equally over two years).

- A one-year apprenticeship programme which has a total of 1,100 hours (800 hours at the Vocational Training Centre and 300 hours in in-industry training).

- There are some VTCs run by other Government departments, such as, the Ministry of Defence, which has two VTCs, the Ministry of Interior, which has one VTC as has the Federal Ministry of Agriculture. In 2016, the Friendship VTC in Amdarman and the Wuhan Technical Institute of China agreed to establish a twinning arrangement between them to share experiences in the field of vocational training. These VTCs operates under the regulations of the SCVTA and may offer three, two and one-year apprenticeship programmes.

- There are also some private VTCs and churches that offer three-, two- and one-year apprenticeship programmes under SCVTA regulations.

Short TVET courses

- A few larger companies have in-house vocational training facilities (for example DAL Group and CTC) offering workplace learning (WPL) courses.

- Private VTCs, churches and NGOs offer various short training courses, which may include competency-based training and youth focused training programmes. Some of these pre-employment courses, duration between 3 to 6 months, offered by VTCs are financially supported by Development Partners (DP). One example of these types of programmes is the “Employment Initiative Khartoum (EIK): Prospects for the future of refugees and the local community / Employment Promotion in Khartoum State (EPiKS)” funded by Germany and the “Youth Employment Skills” programme funded by the EU and Germany. 56Further examples would be the previously mentioned twinning arrangement between the Friendship VTC in Amdarman and the Wuhan Technical Institute of China, and the UNIDO’s ‘Project on employment and entrepreneurship development for migrant youth, refugees, asylum seekers and host communities in Khartoum stage (EEDK – RDPP)’,7 which is developing training to develop national VTEC capacity, through interventions aimed in Haj Yousif, Halfia, Jebel Awlia and Karari8 . This includes a focus on supporting potential entrepreneurs to translate concepts into commercial ventures in the manufacturing and service sectors, and strengthening VTECs Job Placement Services units.

- Recognition of Prior Learning is also delivered through the TVET sector via 'Trade Testing' activity' that is offered by many VTCs. Trade tests can be taken by anyone no matter if they obtained skills through traditional/informal apprenticeship.9

It should be noted that the education system is under review, which may change the formal TVET system. In February 2020, Sudan's national team for the development of a new TVET strategy, led by UNESCO’s Cap-Ed project, initiated a series of meetings focused on strategic objectives of several key areas for a new TVET strategy.10

Apprenticeship in Sudan11

The introduction of formal apprenticeships in Sudan can be traced back to the early years of independence with the support of the then Federal Republic of Germany (early 1960’s) followed by the ‘Apprenticeship and Vocational Training Act of 1974’. More recently, the Labour Code of 1997 established guidelines for in-company apprenticeships:

“Apprenticeships: Employers may give new workers the necessary training to learn a profession or work in a specified period based on the needs and needs of work.

Apprenticeship contracts: Training will be provided through a written contract, which will determine the duration, stages of training and the obligations of both employers and industrial pupils during the training period, provided that the reward of industrial students during training does not deviate from the minimum wage set in the provisions of the Minimum Wage Act of 1974.

End of apprenticeship contract: Employers can terminate an apprenticeship contract if the student is not fit for the job, or is unable to learn satisfactorily12 .”

In 2001 the Vocational Training and Apprenticeship Act was issued in accordance with the Constitutional Decree dated and passed by the National Assembly.13 This Act saw the introduction of regulations, overseen by SCVTA, which created a legal framework governing the delivery of apprenticeships. As mentioned in the previous section, some apprenticeship programmes are offered as part of the formal TVET system, including three-, two- and one-year programmes. It is noted that non-formal training is conducted through a range of courses and delivery models that include elements of WBL.

Despite the introduction of apprenticeship guidelines and a legal framework for apprenticeships, there are still concerns about regulation and the delivery of quality programmes that lead to positive job attainment outcomes, so new approaches are needed.15

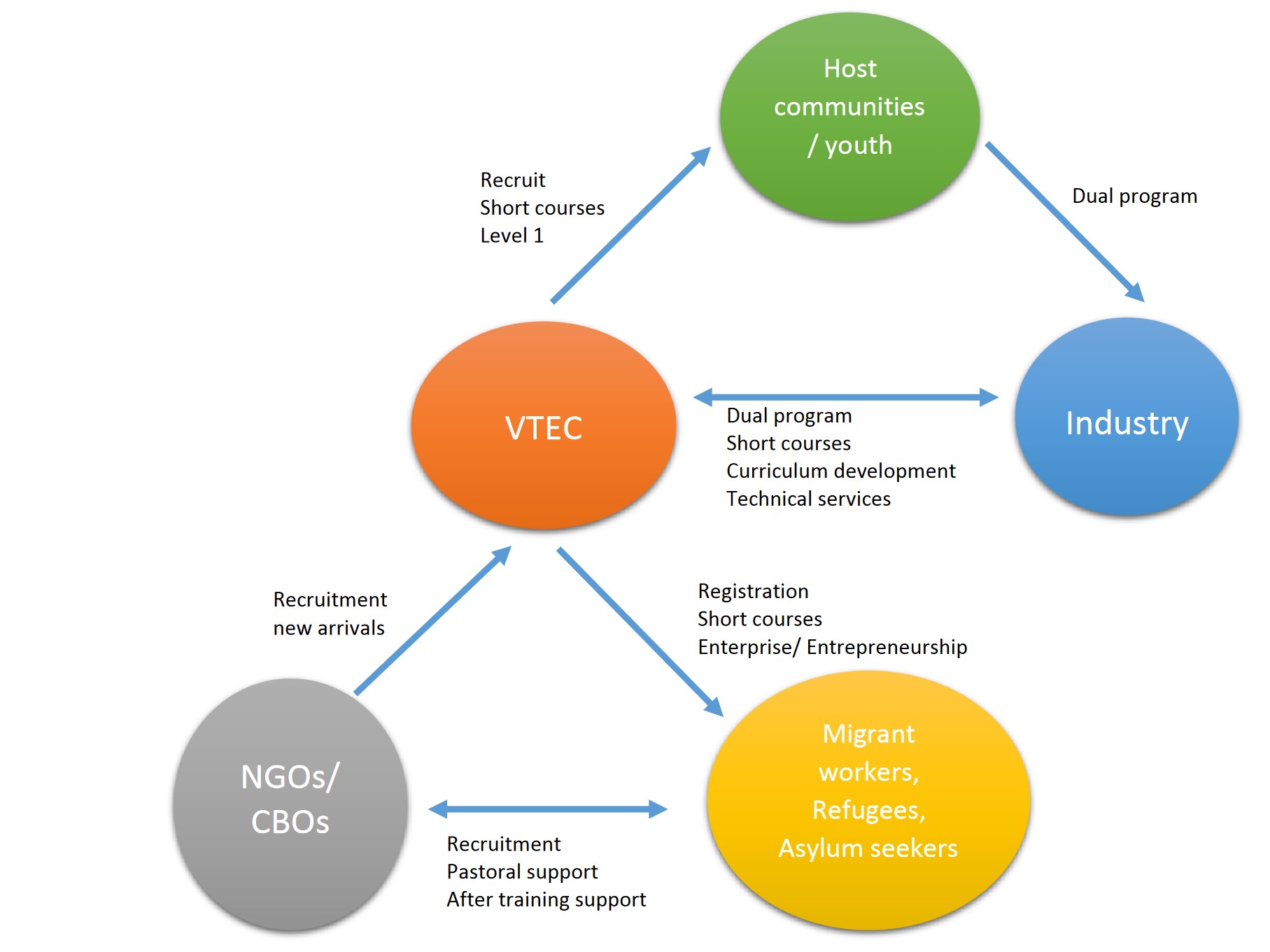

The ‘Employment and Entrepreneurship Development Project for Sudanese Youth, Migrants, Refugees and Host Communities’16 is an example of a TVET intervention that promotes new approaches to apprenticeships.14 In 2017. The project suggested a dual training model called Vocational Industrial Practice Programme (VIPP) which could revitalise apprenticeship in Sudan: ‘The VIPP, as a start for Sudan’s dual training system, should be well-structured and jointly provided by firms/companies for key practical industrial and business training, and the four VTECs for having the responsibility for theoretical know-how and complimentary technical training’17

The VIPP approach, piloted at selected VTC, is based on a 50/50 split between school and in-company training for two- and three-year programmes for youth from host communities. Recognising that not all enterprises, particularly micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs), will be able to provide apprentices and trainees with the breadth and depth of training they require, the VIPP recommends the introduction of formalised collaboration between enterprises and VET centres to support the delivery of WBL that can be delivered at enterprise level. It is hoped that the VIPP model (Figure 2) will support the development of employer-led training by creating an environment that facilitates the contribution of SME

Figure 2 VIPP recruitment and programme structure18

Companies apply to join the VIPP, and the platform establishes a formal contract between the company, the VTC and the trainee is recorded at a VIPP office. In accordance with the contract, the VIPP office will award credits for specified completed training periods , a prerequisite for approving that the trainee can sit for the final exams. The funding model envisages that companies cover the costs of in-company training, whilst the costs for VTC-based training should be partly financed by the public, project (during implementation) and private funds.19

As with the VIPP initiative, a number of vocational apprenticeship courses are offered by the Ministry of Labour and SCVTA supported by different DPs. ILO has played a significant role in supporting Sudan’s TVET sector reforms (with a focus on both formal and informal delivery of training)20 . JICA, through the ‘Strengthening vocational training systems targeting vocational training centres’21 project, has supported SCTVA in establishing certification systems to promote effective work based learning (WBL) in small and medium scale enterprises. UNESCO’s Cap-ED project references the key objective to promote private sector stakeholders’ delivery of training to teachers and students (including employment opportunities) and access to equipment/tools.22

Informal apprenticeship23

As in many other African countries, informal apprenticeships make up the main source for skills development and are often the only realistic skills training opportunity for many young Sudanese. Compared to the formal sector, the informal sector has a much higher absorption capacity of youth entering the labour market. Informal apprenticeships are often delivered by family/friends (traditional apprenticeship) or local artisans through micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) (informal apprenticeship). These informal training models are typically responsive to the short-term skills needed in the local economy/community, which is in contrast to the formal TVET system that tends to be more supply-driven and often lacks relevance to industry skills demand.

Despite the capacity of informal apprenticeships to offer training to a large number of trainees (directed at immediate skills needs), it is a model that comes with significant limitations. There are concerns about quality as the apprentices may not be able to develop competencies beyond those held by the master craftsman, who themselves have gained their skills through informal apprenticeships. It also limits the opportunities for trainees to develop wider knowledge, which is increasingly important as jobs become more technologically driven and fluid. These quality issues will have a negative impact on business productivity and innovation, and trainees’ long term sustainable transition to employment. Informal apprenticeships can also be defined by an absence of agreed training programmes and contractual arrangements between the master craftsperson and the apprentice. This can result in exploitative conditions of long working hours and low pay, which borders on cheap labour and, in some cases, can result in child labour concerns.24

According to findings of an ILO study (2014)25 over 75% of informal apprentices were hired based on a verbal agreement and less than 4% had a written contract. The apprenticeship period varied from 1 to 60 months, often based on how quickly apprentices were able to acquire skills. Most apprentices work more than eight hours a day, seven days a week. In general, no training fees were paid for the training, instead, apprentices would receive wages, often infrequently, or pocket money for their work and tips from customers. These characteristics are believed to represent some of the challenges faced by informal vocational education and training in other African countries.

Initiative: Human Resource Pioneer Firm Certification System

Introduction

The initiative that this report highlights, ‘Human Resource Pioneer Firm Certification System’ (‘the certification system’), was developed through the employment sector strand of the Japanese International Cooperation Agency (JICA) ‘Strengthening peace through the improvement of public services in three Darfur states’ (SMAP – II) project (May 2015 – Nov 2020). SMAP-II aimed to enhance the peace and stability of Darfur through improvement of the public services in four key areas: health, rural water supply, employment and monitoring and evaluation of the public projects. Project activities included conducting pilot projects with an awareness of promoting peace, strengthening the capacity of state government officials, and improving the system for providing administrative services such as the development of guidelines and manuals.

In the employment sector, SMAP-II conducted three types of vocational training as pilot projects.

- ‘Integrated entrepreneurship training for women’ delivered through the Women’s Union focusing on training to support increases in employment and income of young women, especially single mothers and war-widows.

- ‘Human resource development for micro and small enterprises’, delivered through the Craftsman Union (CU) via a one-year training programme for workshop owners and master craftsman (total 120 enterprises) to provide know-how on staff training (including apprenticeships) as well as business management skills. The tool described in this report, ‘the certification system’, was developed through this pilot. SCTVA was the Government of Sudan’s delivery agency for this intervention.

- ‘Vocational training for unemployed youth’ delivered by technical secondary schools (TSS) through three courses in automotive, electrics and welding. The training was characterised by the combination of school-based training and practice at the workplace in a local company.26

How does the initiative work?

The presented initiative is an employers’ guide27 , supporting and encouraging their engagement with the ‘Human Resource Development Pioneer Firm Certification System’ (‘The Certification System’). The certification system has been designed to validate enterprises who satisfy the minimum requirements of an effective in-service training provider to be certified as “Human Resource Development Pioneer Firm” by the Supreme Council for Vocational Training and Apprenticeship (SCVTA). The core objective of the certification system is to provide a mechanism to register and promote enterprises who are consciously and conscientiously training their employees and, by doing so, promoting decent work and improving the social images of workers in MSME industries. The guide provides practical, and importantly, relatable advice for Sudanese employers facilitating their involvement in the certification system. The guide innovatively presents key concepts through the use of an animated ‘comic strip’ style presentation, capturing the story of an employer as he works his way through the certification system process. This includes a rationale for how certification can improve business productivity, presented through dialogues between the employer, his peers, and a representative from the Craftsman Union (CU). These dialogues include challenging stereotypical perceptions of the value of training, for example:

The presented initiative is an employers’ guide27 , supporting and encouraging their engagement with the ‘Human Resource Development Pioneer Firm Certification System’ (‘The Certification System’). The certification system has been designed to validate enterprises who satisfy the minimum requirements of an effective in-service training provider to be certified as “Human Resource Development Pioneer Firm” by the Supreme Council for Vocational Training and Apprenticeship (SCVTA). The core objective of the certification system is to provide a mechanism to register and promote enterprises who are consciously and conscientiously training their employees and, by doing so, promoting decent work and improving the social images of workers in MSME industries. The guide provides practical, and importantly, relatable advice for Sudanese employers facilitating their involvement in the certification system. The guide innovatively presents key concepts through the use of an animated ‘comic strip’ style presentation, capturing the story of an employer as he works his way through the certification system process. This includes a rationale for how certification can improve business productivity, presented through dialogues between the employer, his peers, and a representative from the Craftsman Union (CU). These dialogues include challenging stereotypical perceptions of the value of training, for example:

‘But…What is human resource development really about? All employees become skilled workers by themselves over time, don’t they?

The guide uses the animated dialogues as a platform to provide more detailed reasons for employer involvement in HRD through the introduction of concepts such as the impact of training, the employees’ mind set, an attractive working environment, and a shared sense of vision and responsibility. As well as making the case for employer-led training, the guide provides insights into the characteristics of strong training programmes, including advice on combining on-the-job and off-the-job training, the importance of well-planned training programmes, and approaches to setting tailored training objectives and tasks.

The guide also describes how employers benefit from registration in the certification scheme, including the opportunity to participate in CU-led technical and business training programmes. This rationale references the opportunity for business growth and development through training in areas such as marketing, accounting and human resource management. The guide also highlights how the prestige of a certificated authorised training provider represents an opportunity to attract skilled workers and customers;

‘Skilled workers will be proud of their work and motivated, and customers will also be attracted to the product of your enterprise’.

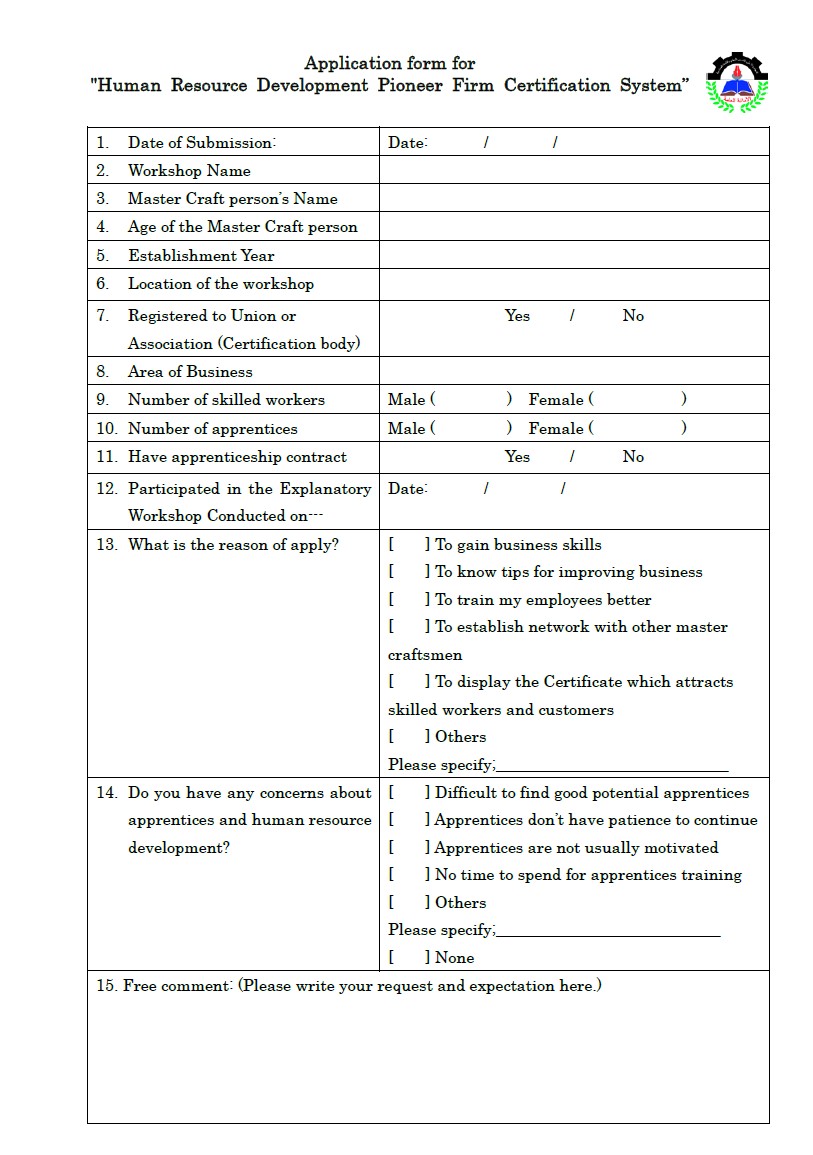

The guide highlights the requirements for certification, including criteria related to CU membership, years of incorporation, use of written apprenticeship contracts and apprentices training plans, and received CU designed training on effective HR development. These criteria are clearly linked to addressing some of the challenges associated with informal training models and demonstrate an innovative approach to embedding practices that would support a more regulated sector. The guide also looks to address employer concerns about the rigour of membership by emphasising the accessibility of certification by collaborative messaging communicated through reassuring animations and dialogues:

Employer: Contract and training plan? What should I do exactly??

CU representative: The process is not complicated, and you can get benefit by following the steps below. Let’s see each step together!!

This is followed by a series of practical steps for the registration process, including helpful checklists, an example apprenticeship contract and the certification scheme application form. This will help to provide a direct link between the guide and the practical steps involved in becoming registered. As can be seen below, the application form is kept simple (only one page) and focuses only on information that is of immediate importance for hiring an apprentice and that the employer can easily complete. . This approach will help to reassure employers about the accessibility of the certification system and reflects an appropriate model for effectively engaging with informal sector stakeholders.

Rationale for the tool

The ambition of the ‘certification system’ to provide an accessible framework for employers to develop more effective, planned and regulated apprenticeship programmes are clearly linked to SMAP-II’s objective to promote peace and stability through prosperity by supporting enterprises to achieve improvement of business management through the effective use of human resources. There has been an absence of schemes focusing on the regulating of Sudan’s informal apprenticeship system and the certification system is an attempt to encourage employers to introduce more formalised contractual and training plans.

The effective implementation of on-and-off-the-job-training is vital for productivity even in challenging and unfavourable economic conditions. As described earlier, MSMEs make up the vast majority of Sudanese industry, and the informal nature of many of these enterprises means that there is limited regulated training for the majority of employees. This can result in challenges associated with informal apprenticeships that have previously been described, including lack of contracts and exploitative conditions resulting from undefined roles and responsibilities. The Sudanese MSME sector can also be characterised by outdated systems and neglect of human resource development, resulting in issues associated with apprenticeship drop out and a lack of relevant skills required for the workplace, or lacking validated certification to demonstrate their learning. Equally, many employers or master craftsmen do not have the business management and HR development skills required to effectively run their businesses. There was also a secondary identified need for the CU to show enhanced membership value, such as managing activities like the ‘certification system’.

- The manual is designed to support skills development in the informal sector by focusing on current practices delivered through informal apprenticeship. The introduction of regulatory processes will help to bridge the gap between formal and informal apprenticeship.

- The use of animated dialogues is an innovative way to present information to employers in a reassuring and accessible manner. The discussing of concepts and processes through the use of peer-to-peer conversations would represent a culturally attractive medium for Sudanese MSME owners.

- The approach is collaborative rather than prescriptive or directive. The guide uses the imagery and language of employers to persuade them of the value of registration, rather than telling them that this is something that they ‘must’ do. This more ‘organic’ bottom up approach to working with stakeholders feels like an appropriate way to access the complicated informal sector. The use and portrayal of identifiable characters, and images, would also help to reassure Sudanese employers that the scheme is ‘for them’.

- The guide also uses accessible language, which would help to impact employers, ensuring that they understand the key concepts. It would also reassure them that the scheme is accessible and not overtly complicated. The use of accessible dialogues provides a platform to present some of the more conceptually challenging input concentrating on business cycles and human resource development.

- The guide also contains guidelines and contract templates that can be used directly by users. This direct link between the guide and practice will be of great value for employer acceptance.

- The JICA delivery team reports that the system was also relatively cost effective, in many cases regulated activities and practice were those that were already occurring in the informal sector.

- The guide was also supplemented by an aligned ‘Organiser’s manual for the prerequisite training28’ course and CD; there are also plans to upload the video to YouTube to increase access.

- The Human Resource Pioneer Firm Certification Scheme is a valuable and innovative approach to applying bottom-up interventions by introducing apprenticeship regulation to the informal economy, an area that is often ignored by development programmes. The certification system uses accessible images and language that clearly explains the rationale and processes for employers to sign up to the scheme. It consciously addresses some of the challenges and concerns held by employers through offering clear rationale for the value of registration.

- The scheme is also clearly aligned with the objectives of the SMAP-II project and offers a workable, and transferable, solution to challenges associated with regulating informal apprenticeships.

- The certification scheme is also closely aligned with models of private sector engagement and carefully works with wider groups of Sudanese stakeholders such as the peer support offered through CU and the regulatory validity offered by SCTVA.

- The need for strong facilitators to deliver the prerequisite training programme and to provide ongoing support for employers in the development of effective apprenticeship plans should not be neglected.

- The guide and certification system can only do "so much"; ultimately, learners' experiences and success depend on their enthusiasm as apprentices and that of their employers to run effective training programmes. The challenge of changing mind sets, and in some cases deeply held concerns about the value of training will take time. The guide and scheme are an important first step to demonstrating the value of more formalised and regulated apprenticeships but cultural shifts in attitudes and behaviours will require ongoing and long-term interventions.

- - The images portrayed are mostly male and the use of characters with greater gender diversity could have led to more inclusive outcomes..

- It should be noted that despite the progress reported in the SMAP-II target regions, the project team report that the certification system has not yet been taken up on a national level, as hoped, indicating that even the most innovative of informal sector interventions take time to gain traction and coverage.

A programme review conducted in 2017 on the first role out of the certification system identified some interesting insights, testimonials and examples of its impact29.

- Participants referenced improvements in HR management, with associated growth in productivity. This included tangible increases in levels of customer services and sales. There was particular emphasis from employers (Khartoum and Nayala) on the value of the management training in designing apprenticeship training programmes. Employers also referenced the motivational impact of the scheme both on them and their apprentices.

- There were reports of improved skills, attitudes and discipline resulting from the design and delivery of more formalised and regulated apprenticeship programmes developed through the scheme.

- Apprenticeships showed increased motivation based on the financial and working condition improvements derived from the contractual agreements developed through the scheme. Apprentices also showed more interest in completing training programmes; this improved retention was attributable to reasons linked to certification, finances and an increased sense of obligation to their employers.

- The scheme also encouraged increased employability, entrepreneurial and business skills amongst trainees. One employer noted; ‘Currently while we are attending the training the apprentices are managing the workshop’. An employer from West Darfur told how his apprentices started to set up a small parts business in the employer's workshops, encouraged by the owner who saw this as a means to encourage trained apprentices to continue working for him.

The programme has also encouraged employers to think about how they can use the programme and their apprentices to introduce innovative approaches in their business. A good example of this development is one employer, Monjid Cars, which, with the help of young female apprentices, has launched the 'Miss Monjid' initiative30 , which uses female roadside assistance workers to provide service to women drivers.

The programme has also encouraged employers to think about how they can use the programme and their apprentices to introduce innovative approaches in their business. A good example of this development is one employer, Monjid Cars, which, with the help of young female apprentices, has launched the 'Miss Monjid' initiative30 , which uses female roadside assistance workers to provide service to women drivers.