Procedures and Guidelines: Implementing work-integrated learning (WIL) policy

Initiative focus

This tool is aimed at outlining procedures, funding mechanisms and responsibilities for the delivery of relevant and quality driven apprenticeships and industrial attachments

Target group

Employers planning to hire apprentices, prospective apprentices/trainees, TVET providers (TVETPs) partnering employers in the delivery of apprenticeships, industry mentors, Namibia Training Authority (NTA) officials

TVET in Namibia

Introduction

Namibia’s economic growth is threatened by its dependency on low productivity sectors, a vulnerability that has manifested itself with high levels of youth (15-34 age group) unemployment, measured at 46.1% in 20184 . The need to utilise Namibia’s human resource through an efficient and effective TVET system is captured in the country’s ‘Vision 2030’ which anticipates the transformation of the Namibian economy into an industrialised and knowledge-based economy. Vision 2030 is being delivered through a series of National Development Plans, which include TVET objectives related to:

- Increased enrolment, resourcing, capacity and provision

- Linking to key priority sectors and enhanced pathways to general education

- Enhanced sector leadership, management and quality

- Increase private sector engagement in the TVET system to promote relevance and credibility

- Improved financing, including linking funding to performance and outcomes

- Introduction of competency-based education and training (CBET)

The Government of Namibia (GoN), through the Ministry of Higher Education, Technology and Innovation (MHETI), is enhancing TVET quality and relevance through the introduction of more effective models of Work Integrated Learning (WIL), which is equitable to work-based learning. This initiative includes the National TVET Policy, MHETI (2021), with the objective to establish a sector defined by; increased private sector engagement, improved administration, performance linked funding, access and inclusion, utilisation of RPL models and enhanced linkages between TVET and the wider education sector5 . Namibia’s strategic vision for WIL is now been translated into reality through the design of Namibia’s Work Integrated Learning Policy6 , which is being developed under the leadership of the Namibian Training Authority (NTA)7 . This includes the realisation of WIL policy objectives linked to 8:

- Establishing a WIL framework for TVET

- Promoting increased TVET access and inclusion

- Introducing financial incentives for employer engagement in apprenticeships and industrial attachments

- Utilising Namibia’s training levy to promote quality WIL delivery and models

- Increasing TVET credibility and relevance to address skills mismatches and facilitate the transition to employment

NTA has launched and oversees WIL guidelines and procedures (guidelines), funded through the levy, that promote the realisation of these objectives. It is this initiative that this report describes.

Background

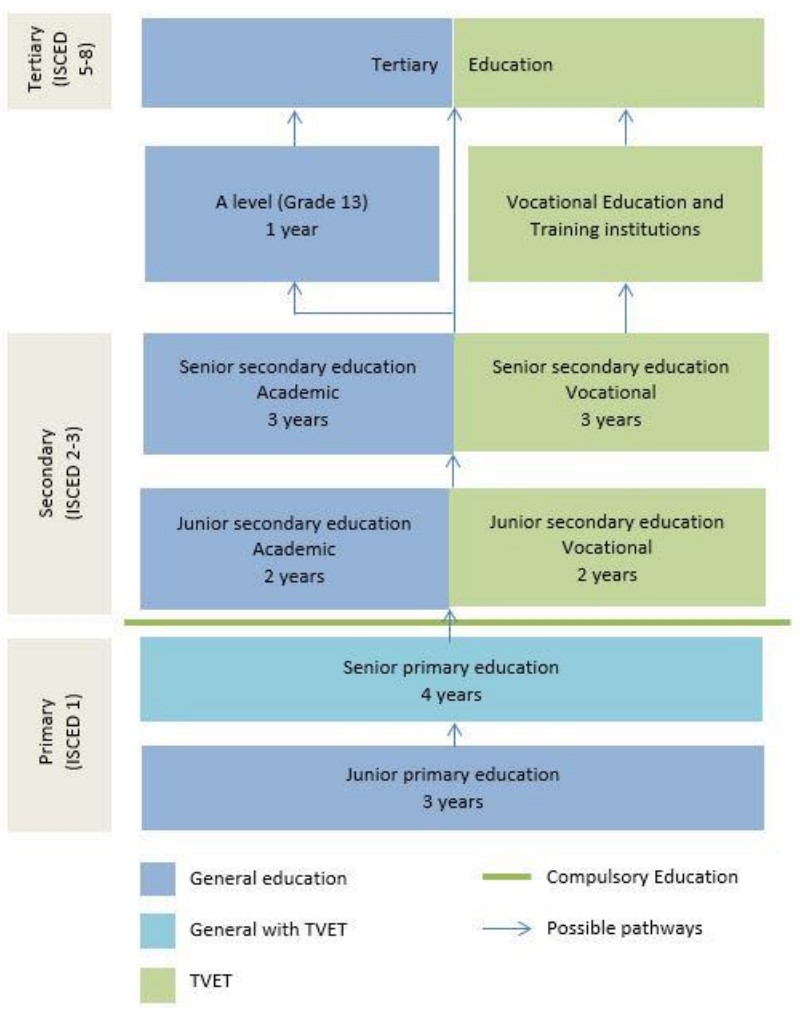

Formal VET9

TVET is introduced into the curriculum at the junior secondary education level, through a pre-vocational and technical stream, which allows students to choose three TVET related elective subjects including from: agriculture; computer studies; design and technology; accounting; entrepreneurship; visual art; integrated performing arts; hospitality; and subjects covering metalwork and welding, woodwork, construction, electricity and electronics. At the senior secondary education level, students can take a number of core curriculum subjects as well as some electives, including technical and vocational subjects. At Grade 11 students receive the National Senior Secondary Certificate Ordinary and may proceed to Grade 12, which includes the option to attend programmes at vocational education and training institutions, or enter the labour market. TVET programmes at the tertiary level are offered at the Namibia University of Science and Technology (NUST), however, there is disconnect between NUST programmes (L6) and those delivered in TVET institutions (L3)10 . Generally, there are a lack of formal pathways between TVET and the wider education system. There are also a limited number of technical schools which offer both technical and general routes, this lack of provision is currently being addressed by NTA, including through the delivery of the Growth at Home Strategy and the Harambee Prosperity Plan (HPP) that calls for collective intervention to skills development to address skills mismatches across most economic sectors in Namibia.11 There are also a lack of pathways between TVET (formal and non-formal) and general education, and even between NUST and TVET centres, due a lack of coverage of levels 4 and 5. The provision of TVET at these two levels is also an NTA priority.

The Namibian TVET System

Source: World TVET Database, Namibia (UNEVCO 2015) https://unevoc.unesco.org/wtdb/worldtvetdatabase_nam_en.pdf

There are also challenges resulting from the limited relevance of TVET to the labour market. This is part due to the difficulty in finding job placements to support WIL practical experience. Due to the frailty of Namibian small and micro-enterprises and the paucity of larger, formal firms, TVET sector trainees struggle to find placements, or when they do, quality ones. Trainees who do not find a placement lack initial work experience and are disadvantaged when they enter the labour market. At present, the challenge is most serious for trainees at lower levels of the NQF and in centres lacking established relationships with firms. There are also issues with gender-based discrimination from employers, for example, garage owners refused female trainees in car mechanics12 . This emphasises the need for a policy of incentives for firms to take trainees and the introduction of a formalised process for job placements (instead of the current fragmented approach).

Non-formal VET

Non-formal TVET programmes in Namibia are provided by the private sector, non-government organisations (NGOs), religious organisations and vocational training and community skills development centres (COSDECs). NGOs and religious organisations tend to target socio-economically deprived sections of society offering TVET programmes to unemployed youth, women and the disabled13 . COSDECs, run by the Community Skills Development Foundation (COSDEF), offer short-term TVET programmes. There are issues with trainees from non-formal TVET, for example form COSDEC’s, being unlikely to be admitted to formal centres for further skills development.14

The introduction of WIL procedures and guidelines can be seen as a response to calls for the transformation of the existing TVET system.15 Provision is often insufficient to meet demand with fragmented approaches between different providers. There are issues with retention, relevance, funding and quality.

The Initiative: Procedures and guidelines for the implementation of work-integrated learning policy in Namibia

Background

The apprenticeship intervention described in this report is a series of procedures and guidelines (‘guidelines’) that have been developed by NTA to support the implementation of the strategic objectives and mitigate challenges outlined in the previous section. The guidelines outline procedures governing the planning, implementation, monitoring and management of the WIL Policy and provide a framework that promotes; ‘collective intervention to skills development to address skills mismatches across most economic sectors in Namibia’16. An important element of these guidelines is that they are linked to funding (drawn from Namibia’s training levy) that apprentices and employers can access for WIL delivery17 . This will have a significant motivational impact for the update of the guidelines and demonstrates how funding can be utilised to drive strong WIL practice.

The initiative’s key strategic objective to promote private sector engagement and training relevance through models that facilitate the re-introduction of apprenticeships and formalise WIL. This includes through defining key roles for workplace mentors and training providers (TVETP) to ensure the delivery of both theoretical and practical training in the development of technical, soft and ethical skills and competencies. Private sector engagement in the initiative has also promoted through the use of pilots in the guidelines’ development to ensure that ‘meaningful social dialogue was undertaken to establish sustainable relationships with employers and to obtain clear market relevance on implementing formal apprenticeship’. The conducted pilots also tested the capacity of TVETPs to respond to labour market demand, and the effective allocation of financial incentives to promote employer engagement.

Procedures and guidelines for the implementation of Work Integrated Learning (WIL)

The initiative looks to realise the defined objectives through a series of guidelines. This includes defining apprenticeships through a framework of requirements:

- An apprentice is an employee in training – making the integral link between employment and training

- Employers must register with NTA to join the apprenticeship scheme – providing an opportunity to regulate the participating employers

- There needs to be a formal agreement between the apprentice and employer. This must include a training implementation plan specifying qualification training arrangements – defining roles, responsibilities and expectations

- Apprentices will receive a minimum remuneration based on an NTA approved apprenticeship grant

- Apprenticeships must be based on a qualification registered on the NQF and apprentices/trainees must be issued a national vocational certificate on successfully completing their WIL course – supporting enhanced links between TVET and wider education sector and promoting pathways for learners

- Theoretical training must be conducted by a registered and/or accredited TVETP – quality assuring the theoretical part of WIL courses

- Assessments must be conducted by registered and/or accredited TVETPs, assessment centres or approved workplaces – ensuring the validity of apprenticeship qualifications

The guidelines further operationalise these requirements by defining roles and responsibilities for WIL stakeholders. In the case of employers, this includes reference to being sufficiently equipped and resourced for apprenticeship training, development of staffing plans to include apprentices in future HR planning, collaboration with NTA to ensure familiarisation with national qualification requirements and engagement with TVETPs to agree training contents and costs. The focus on NQF L4 is also designed to address the current gap in TVET qualifications at this level.

The guidelines also provide advice on WIL procedural requirements. These includes reference to participating employers submitting mandatory documents; application form, registration certificates, mentors’ experience and qualifications, health and safety and social security certification, evidence of VET levy payment (if applicable) and confirmation from partner TVETP.

- NTA workplace approval process which needs to be completed before apprentices are appointed and requires evidence of:

- Tools and equipment

- Health and safety procedures

- Qualified and experienced mentors and appropriate mentor/apprenticeship ratios that ensure training safety and quality. This includes through the use of an apprenticeship induction that covers (but not limited to):

- Occupational health and safety

- Environmental safety

- Welfare and industry requirements

- Appropriate recording systems and communication facilities

- Limits on appointed apprentices based on company size

- NTA approval details which define key aspects of the approved apprenticeship (WIL):

- Approved qualifications and level

- Maximum number of apprentices and any conditions

- Feedback for employers who have not been approved

- Details of apprenticeship agreements:

- Roles, responsibilities, conditions and obligations and associated corrective measures

- Duration and training implementation plan (including milestones and partner TVETP’s training schedule). Apprenticeship duration guidelines include:

- Duration to be determined by qualification requirements

- Minimum duration of three years for an NQF L4 qualification

- Employer and TVETP need to agree on duration of practical/theoretical input for each qualification based on a 70:30 ratio

- Information of the agreed apprentices’ training grant and qualifications being trained towards

- Entry requirements:

- Namibian citizenship and aged 16-35

- Certified physically fit to perform work required in apprenticeship role

- Meets employer, qualification and TVETP entry requirements and isn’t duplicating a previous apprenticeship and/or qualification or NTA funding

- Reference to potential dispensation on requirements for learners from marginalised groups to increase WIL inclusivity

- NTA monitoring and support role:

- NTA conduct a minimum of two monitoring visits to employers during their first year of training. Visits include meetings with training coordinators, supervisors, apprentices and their Mentors to ascertain areas of support where required.

- The first visit is described as ‘Advisory and Support’, in which the NTA provides advice on; workplace learning and logbook usage, apprentices’ and mentors’ performance, and associated recommendations.

- The second visit is described as ‘Compliance’, in which NTA checks WIL progress, reviews the implementation of initial recommendations.

- NTA visits are also linked to releasing of apprenticeship funding payments.

- Mentors:

- Appointed apprenticeship mentors and trainers should attend NTA induction workshops

- Mentors should possess a minimum of a L4 qualification and have three years relevant experience.

- Mentors’ responsibilities in WIL include;

- Facilitating and assessing learning against outcomes

- Mentoring and coaching of apprentices, including preparing for summative assessment

- Keeping records (including supervising apprentices’ logbooks) and liaising with TVETP partner

- Monitoring and Reporting:

- Employers need to establish monitoring and reporting systems that allow them to accurately map apprentices’ progress

- TVETPs and employers collaborate on developing approaches that facilitate apprentices’ success and develop remedial plans for trainees who are failing to meet milestones.

- TVETPs and employers must inform NTA of risks to successful completion and mitigating activities

- Assessment:

- Overview of the use of logbooks

- Required links to NQF Awards

- NTA established database of apprentices/trainees who have successfully completed their WIL programme

- Assessment eligibility criteria

When promoting apprenticeship to employers a simpler version of the above-presented stages is used.

Funding

A particularly innovative aspect of this NTA apprenticeship initiative is the funding model that underpins its delivery. Once the guidelines have been met and approved by NTA, employers and apprentices can assess funding through Namibia’s training levy. This will incentivise employers and apprentices to conduct WIL under NTA’s framework and helping to drive training that meet Namibia’s identified TVET challenges. Funding through the initiative includes:

- A grant of N$53,600-00 per annum for employers who employ an apprentice. There is also an opportunity for NTA to increase allocated grants to reflect the intensity of the target occupation. The grant assists employers in paying a minimum monthly wage (allowance) to apprentices and make a contribution to training fees. The grant will also reduce the burden of costs for employers during the early stages of the apprentices training programme as they move towards productivity.

- The funding arrangement for apprenticeships is included in the memorandum of agreement (MoA) signed between the NTA and employers. This will help to formalise the payment and link it with the delivery of the agreed apprenticeship for the (minimum) three-year duration of the programme.

- Importantly, grant payments will be paid out in four annual tranches depending on the meeting of key deliverables:

- Tranche 1 (25%): released after first 30 days of the apprenticeships subject to: NTA approval of apprenticeship agreement, workplace induction, identification and communicating of skills gaps by employers for TVETPs to address and setting of apprentices’ training implementation plans

- Tranche 2 (25%): released after the completion of first three months of the WIL programme, subject to: satisfactory training progress report. This is the last opportunity to replace any apprentices who are not making sufficient progress.

- Tranche 3 (40%): released to the employer subject to: receipt of TVETP performance report, and employer progress monitoring report, indicating that the apprentices have completed 60% of their qualifications and programme. The amount of payment will be based on the level of apprentices’ progress with qualifications and performance. This will be assessed through evidence gathered via logbooks, TVETP performance reports and NTA monitoring visits.

- Tranche 4 (10%): released after the submission of the closure report which captures the completion of apprentices’ individual learning programmes and potential employment opportunities. This includes linking payment based on apprentices’ proven competence in the target occupation and qualification.

- Apprentices also receive funding support via a minimum monthly allowance of N$ 2,500, additional funding remaining from the employer grant can be used to fund their contribution and develop training facilities, during the duration of the WIL programme. Employers and apprentices can agree a higher rate which should be recorded as part of the apprenticeship agreement.

- Off-the job training delivered at the TVETP or employer should be treated as part of the Apprentice’s normal paid working hours

- Employers receive an additional grant of N$ 20,000.00 for hiring an apprentice with disabilities. It is intended that this grant should be used to develop companies’ facilities to ensure to facilitate access for apprentices with disabilities.

The guidelines also include mandatory procedures for the design and delivery of industrial attachments and recognition of prior learning (RPL).

- The use of levy funding aligned to monitored procedures will both promote stakeholder engagement and help to ensure their compliance with models of good WIL practice.

- The guidelines show a national agency (NTA) taking clear ownership and leadership of WIL policy and practice. Although the guidelines borrow from international TVET concepts, the initiative has distinct Namibian features and focus, which should facilitate commitment and engagement from different stakeholders.

- The guidelines are clearly aligned with identified needs in terms of increased job placements, relevance and credibility, quality, stakeholder collaboration and employer engagement. In this regard, they can be seen as an innovative approach to the operationalisation of GoN strategic objectives.

- The combination of procedures and funding will provide a strong foundation and structure to support the involvement of SMEs and Micro businesses in WIL. The limiting of the number of apprentices to the size of business will also provide a guide to an appropriate level of engagement and mitigate risks of smaller businesses over extending their involvement.

- The guidelines provide a framework for stakeholders (NTA, employers, TVETPs) to collaborate in the delivery of effective WIL, mitigating current challenges with adhoc and fragmented delivery.

- The initiative has been developed on a consultative approach and tested through the effective use of pilots.

- The guidelines clearly define what is meant by an apprenticeship, including referencing payment and contracts (agreement) between key stakeholders. The defining of apprenticeships, linked to funding, will help to embed a shared understanding of quality WIL models and responsibilities. The setting of a minimum three-year period for an apprenticeship will also ensure that they are viewed as a long term and significant programme and qualification.

- The linking of apprenticeships and WIL to NQF qualifications will help to address issues with pathways between TVET outcomes and general education. It will also help to promote a parity of esteem between WIL and general education. The mapping of apprenticeships to NQF L4 will also address current gaps at this level for TVET qualifications and allow for progression to Higher VET. The guidelines include funding opportunities and procedural dispensation to promote the embedding of Gender Equality and Social Inclusion values in Namibia’s apprenticeship model. However, this seems to be on a ‘voluntary’ basis and it appears a missed opportunity not to have included more mandatory inclusion targets in the guidelines.

- Innovative use of funding that is linked to quality assurance monitoring and apprentices’ outcomes, including using key metrics to measure enrolment, retention, progress, achievement and employability. The minimum apprenticeship grant will also support retention and achievement. The use of staged funding also provides a tool through which the guidelines can be enforced.

- The guidelines provide an excellent example of how policy can be translated into practice. This process is now being further progressed through the development of NTA developed operational manuals aligned with the guidelines.

- The guidelines start to establish basic incentives and conditions for WIL, this will start to address some of the challenges associated with non-formal/informal deliver. The guidelines also reference working conditions, termination terms and health and safety, and trainee wellbeing. This includes limiting the number of apprentices employed in higher risk roles.

- The guidelines set out clear roles and responsibilities for the delivery for WIL, however, there is a risk that some stakeholders will need further development for them to fulfil their allocated roles. Although stakeholders will look to follow the procedures, if only to meet funding requirements, there could be a big jump from current practice. For example, will TVET-and employer mentors have the capacity to develop, deliver, monitor and assess apprenticeship programmes, as described in the guidelines. However, the defining of apprenticeship roles will provide an excellent focus for additional capacity building activities, which have already been initiated through the NTA employer mentor induction.

- It would be valuable to have further information on how the implementation and impact of the guidelines will be monitored and measured.

- The monitoring of the guidelines will require considerable NTA resource, expertise and expense. It will be essential that the NTA is appropriately funded and resourced to deliver its governance role.

- Despite the structures and funding put in place to facilitate SME input there are still challenges and issues related to their capacity to engage with WIL.

- The initiative is levy dependent and additional advocacy activities will be required to secure a level of employer input that would make it a sustainable model.

As part of this study, GOPA consultants met with NTA representative, Dalia Mwiya, Manager: Work Integrated Learning (WIL), to discuss the rationale for the guidelines.

Ms Mwiya explained in detail how NTA are determined to promote employer engagement in TVET and introduce enhanced quality assured WIL models, including through the innovative use of levy funding to support good practice. She also referenced the need to design a framework through which different WIL stakeholders could collaborate. She spoke about the need to link WIL outcomes employment and potential progression to general education through mappable pathways linked to the NQF and the importance to operationalise the GoN’s strategic objectives for the TVET sector. She described the key role played by NTA in both monitoring and promoting the guidelines, how it is envisaged that the authority will drive Namibia’s apprenticeship agenda. She also described NTA developed tools (apprenticeship logbook, application form and promotional materials (‘brochure’ and ‘booklet’) which will be used to further operationalise and promote the uptake of the guidelines.